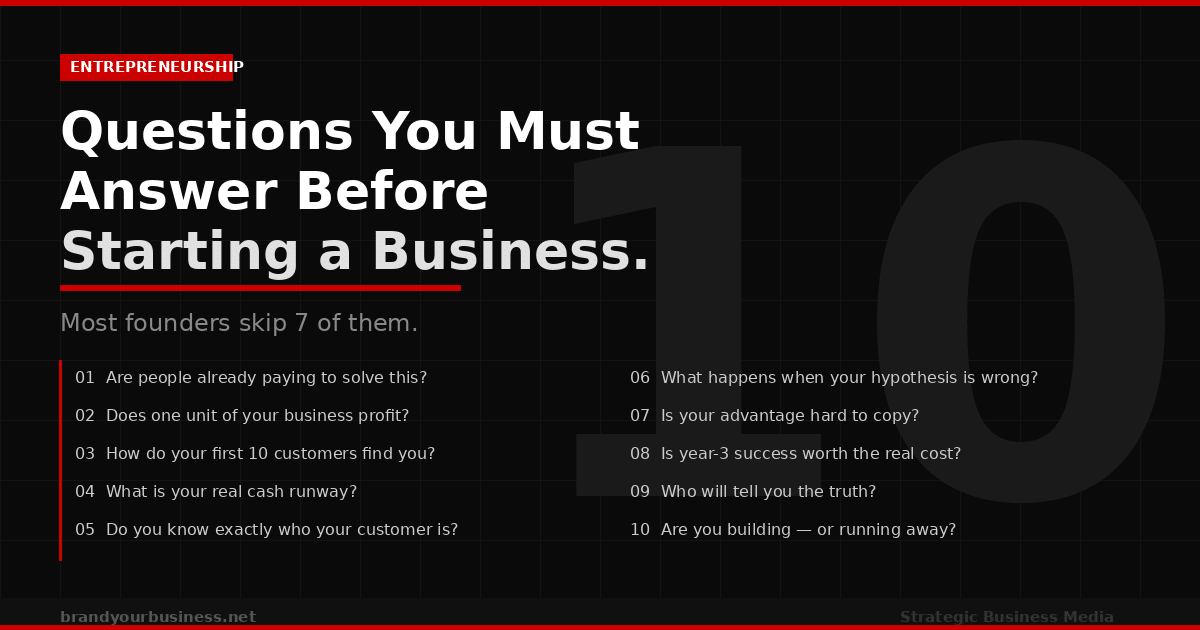

If you’re searching for what to ask before starting a business, most checklists will give you the safe version: “Do you have passion? Do you have savings? Have you written a business plan?”

That’s not what this is.

The questions most founders skip aren’t about passion or planning. They’re about structural reality — the uncomfortable gaps between what you think your business will be and what the market will actually allow it to become. According to the U.S. Small Business Administration, roughly 20% of new businesses fail within their first year and nearly 50% close within five years. Most of those failures aren’t from bad luck. They’re from decisions made before the business ever launched — decisions that looked fine at the time because nobody asked the right questions.

These 10 questions won’t guarantee success. But if you can’t answer them clearly before you start, you’re not ready to start.

Question 1: Are You Solving a Problem People Are Actively Paying to Solve Right Now?

Not a problem they “would probably pay for.” Not a problem they’ve told you exists. A problem they’re already spending money to solve — just badly, expensively, or incompletely.

This distinction eliminates most business ideas immediately.

If potential customers are already paying competitors — even imperfect competitors — you have evidence of a real market. The job is to do it better, cheaper, or for an underserved segment. That’s a winnable game.

If nobody is currently paying anyone to solve this problem, you face a different and much harder challenge: you’re not competing for market share, you’re trying to create a market from scratch. Most founders who attempt this underestimate the cost in time, capital, and psychological endurance. A small minority succeed. Most don’t.

The honest test: Name three competitors. If you can’t, either you’re operating in a genuinely new category (rare, and risky) or you haven’t looked hard enough (common, and correctable).

For a deeper look at why most business ideas collapse at this exact point, see why small businesses fail — the number one structural error is building products the market never actually requested.

Question 2: What Does One Unit of Your Business Actually Cost to Deliver Profitably?

Most founders think about revenue first. The ones who survive think about unit economics first.

Unit economics is simple: what does it cost you to acquire one customer, deliver one product or service, and retain that customer long enough to make the relationship profitable? If that math doesn’t work at a single-unit level, it won’t fix itself at scale. Bigger numbers make profitable operations more profitable and unprofitable operations more catastrophic.

The calculation:

- Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC): what you spend in marketing, sales, and time to get one paying customer

- Cost to Deliver (COGS): what it costs to fulfill the product or service

- Lifetime Value (LTV): total revenue that customer generates before they leave

- The ratio that matters: LTV must significantly exceed CAC + COGS

If your LTV/CAC ratio is below 3:1, you have a structural problem that growth will amplify, not solve. Many founders discover this 18 months and $200,000 in, when it’s too late to pivot cleanly.

Answer this question with real numbers — even estimates — before you start.

Question 3: How Will Your First 10 Customers Find You?

Not your first 1,000. Not your eventual marketing strategy. Your first 10.

This question separates founders who understand distribution from founders who believe “if you build it, they will come.” Most businesses die not because the product was bad but because nobody heard about it. Distribution is often harder than product development — and founders systematically underplan for it.

Your answer should be specific, not aspirational. “Social media” is not an answer. “SEO” is not an answer for month one. “Posting content” is not an answer.

Specific answers sound like: “I have three former clients who’ve already expressed interest.” Or: “There’s a professional community of 4,000 people in this niche and I know the moderators.” Or: “I’ll cold-email 200 specific companies in this vertical and here’s my exact message.”

If you can’t name the channel and the mechanism for your first 10 customers, your go-to-market plan is incomplete.

Question 4: What’s Your Minimum Viable Cash Runway — and Do You Actually Have It?

Most founders dramatically underestimate how long it takes to generate consistent revenue and dramatically overestimate how quickly they’ll reach profitability.

Cash runway is the number of months you can operate before running out of money. The calculation: current cash reserves divided by monthly burn rate (fixed costs + variable costs at projected operating level). Most experienced operators recommend a minimum of 18-24 months of runway before launch — enough to get through the inevitable slower-than-expected early traction, one or two failed experiments, and an unexpected cost you didn’t plan for.

If your runway is 6-9 months, you’re not starting a business. You’re betting that everything goes right immediately. Rarely does.

Honest question: If revenue is 50% of what you projected in month six, can you continue operating without panic-mode decisions? If no, you either need more capital before you start or a significantly leaner cost structure.

For more on building financial systems that survive reality, see small business financial management.

Question 5: Who Specifically Is Your Customer — and Have You Talked to Them This Week?

“Small business owners” is not a customer. “Millennials who care about sustainability” is not a customer. A customer is specific enough that you could find 50 of them on LinkedIn in 20 minutes and write them a message they’d actually open.

Founders who can answer this question precisely have usually done primary research: direct conversations with the specific people they intend to serve. Not surveys. Not Reddit threads. Actual conversations where they’ve heard the exact language customers use to describe their problems, the alternatives they’ve already tried, and the price they’re currently paying (in money, time, or frustration).

Founders who can’t answer this question precisely are building based on assumptions. Some assumptions are correct. The ones that aren’t will cost you months and significant capital to discover.

Minimum standard before launch: 20 direct conversations with people who match your ideal customer profile, where you listened far more than you pitched. If you haven’t done this, do it before you write another line of code or spend another dollar on product.

Question 6: What Will You Do When Your Initial Hypothesis Is Wrong?

Not if. When.

Some part of your initial business thesis will be wrong. The pricing will be off. The customer segment you targeted won’t convert. The feature you thought was critical will be ignored. The channel you planned to dominate will underperform.

This isn’t pessimism — it’s what the data shows happens to almost every business in its first year. The founders who survive aren’t the ones who got everything right. They’re the ones who built the psychological and financial capacity to absorb being wrong, learn fast, and adjust without collapsing.

What this requires practically:

- Enough runway to run at least three iterations of your core hypothesis before running out of money

- A system for capturing what’s working vs. what isn’t (not just feeling your way through it)

- The psychological separation to kill ideas you love when the data says they’re not working

If you’ve built your business plan around a single scenario where everything works as projected, you’ve built a fragile plan. The real question isn’t “will something go wrong?” It’s “when it does, am I structurally prepared to respond?”

Question 7: Is Your Competitive Advantage Something Competitors Can’t Copy in 6 Months?

If your answer to “why will customers choose you over alternatives” is “better quality,” “better service,” or “lower price” — you don’t have a competitive advantage. You have a positioning statement. Those can be copied by anyone with time and money.

A real competitive advantage is structural. It comes from things that are genuinely hard to replicate: proprietary technology, a unique distribution channel, a network effect that strengthens with scale, deep domain expertise accumulated over years, a brand with authentic trust built into a specific community, or cost advantages from operational systems that took years to build.

Most early-stage businesses don’t have a structural competitive advantage yet — and that’s survivable. But you need to know what you’re building toward, and you need a clear theory for why your advantage will become defensible before better-resourced competitors notice your market and enter.

The test: If a well-funded competitor decided to copy your exact business model tomorrow, what would stop them from out-executing you within 12 months? If your answer is “nothing,” you need a clearer path to differentiation.

Question 8: What Does “Success” Actually Look Like in Year 3 — and Is It Worth What It Costs to Get There?

Most founders have a vague vision of success: “growing,” “profitable,” “making an impact.” That’s not a destination — it’s a direction. Without a specific definition of success, you can’t make coherent decisions about which opportunities to pursue and which to ignore.

Define it specifically: target revenue, customer count, team size, geographic reach, and what your personal role looks like. Then calculate what it actually costs to reach that definition — in capital required, hours per week for years, relationships strained, personal income foregone during the build phase, and skills you’ll need to develop or hire.

Some founders do this calculation and conclude the destination is worth the cost. Others discover they were romanticizing entrepreneurship without accounting for the actual price tag.

Neither outcome is wrong. But making this calculation before you start means you’re entering with eyes open, not discovering 18 months in that you’ve been building toward a destination you don’t actually want.

For more on the psychological reality of what building a company actually costs, see founder burnout and the CEO psychology trap.

Question 9: Who Will Tell You the Truth When You’re Making a Mistake?

Every founder needs at least one person in their life who will tell them when they’re wrong — not to be supportive, not to be encouraging, but to tell the actual truth about what they’re observing.

Most founders surround themselves with people who are either too invested in their success (co-founders, employees, investors who’ve already committed) or too removed from the business to have informed opinions (family, friends who are rooting for you). Neither group is well-positioned to give you the honest, informed feedback you need when you’re heading in the wrong direction.

The most valuable people in a founder’s orbit are those with direct relevant experience, no financial stake in your outcome, and enough respect for you to say “this isn’t working and here’s specifically why” without softening the message to protect your feelings.

Before you start: Identify two or three people who fit this description and who’ve explicitly agreed to play this role. If you can’t name them, building that relationship is as important as any other pre-launch work.

Question 10: Are You Starting This Business Because It’s the Right Opportunity — or Because You’re Running Away From Something Else?

This is the question most people skip because it requires the most honesty.

Some people start businesses because they’ve identified a genuine market gap they’re well-positioned to capture. Others start businesses because they’re miserable in their current job, need to feel in control of something, want status, or need to prove something to people who doubted them.

Both types of founders start businesses. The first group has a significant structural advantage. The second group can still succeed — but usually only if they’re honest about their motivation and willing to examine whether they’re making decisions in service of the business or in service of the psychological need that pushed them to start it.

“Escaping” is a valid motivator to start, but it’s a dangerous compass for the decisions that follow. Businesses built around the founder’s need to feel significant tend to resist the structural changes those businesses eventually require — like bringing in stronger operators, stepping back from decision-making, or killing a product line that feels personally meaningful but isn’t commercially viable.

The honest question: If this exact business opportunity existed but someone else was running it and you could join as employee number three — would you join? If the answer is no, you might be more attached to being the founder than to building this specific business.

Before You Start

These 10 questions don’t require perfect answers. They require honest ones.

Most founders who fail didn’t lack intelligence or effort. They lacked honest pre-launch thinking — specifically about unit economics, distribution, runway, competitive advantage, and their own psychology. They optimized for starting fast instead of starting right.

Answering these questions thoroughly before you launch won’t eliminate risk. But it will eliminate the most predictable and most preventable reasons businesses collapse — and it will give you a clearer map for the first two years when clarity is most scarce and most valuable.

If you can’t answer all 10 cleanly today, that’s useful information. It tells you exactly where to focus next.

Leave a Reply